On Oppression of Russian Language in Ukraine

Mariam Naiem · 14 Sep 2022 · Adapted from original Twitter thread

A decade-old pretext of Russian wars is the “protection of Russian speakers from oppression”. What does this “oppression” look like? In this essay, I use my personal experiences to shed light on this and Russian cultural hegemony.

I was born and raised in Kyiv in a Russian-speaking family. My father wasn’t fluent in Ukrainian, so Russian was the primary language at home. He did not have to use Ukrainian because everyone could speak Russian. TV and movies were in Russian. Most popular culture products were in Russian: books, music, movies and their voiceover, magazines, TV shows, and news. They were either made in Russia or made in Ukraine but in Russian.

Although the primary language in schools was Ukrainian, it wasn’t cool to speak Ukrainian among kids. Most of us spoke Russian. A classic case of cultural relations between a colony and empire: the language of the metropole is cultivated as the better and the “civilized” one.

Once, as a kid, I discovered that some of my classmates speak Ukrainian at home. “Oh, it must be because they are from villages or have relatives there.” This was my explanation that some kids didn’t speak Russian at home. Of course, I’m talking about a specific region (Kyiv) rather than all of Ukraine, but this attitude has undoubtedly existed for years in many places in Ukraine.

The culture and policies of the Russian nominal empire and the USSR (most of the time) imposed the idea of the Ukrainian language as the language of the village and the less civilized and less educated.

Another topic of teenage complaints was Ukrainian literature: it was always about our nation’s never-ending struggle. We didn’t understand this, and of course, I compared the literature to the Russian one, thinking about how the latter is more developed.

This is an example of cultural alienation: devaluation and rejection of one’s own culture, and seeing value in a different, dominant, imposed culture of their colonizers. The description of Ukrainians and the Ukrainian language as funny and silly in the books of Turgenev pushed me to consider myself more Russian than Ukrainian. Because I didn’t want to be that funny Ukrainian. The comedic behavior is one of the invariant components of the Russian stereotype of a Ukrainian: funny people who sing and dance a lot and speak in a funny “dialect”.

Another component is “natural life.” For Russians, who see themselves as “civilized,” Ukrainians are “people of nature.” This “civilized person” looks down with a smile at the behavior of their “younger brother,” “not affected by culture.” This is the crucial contraposition at the core of the Russian stereotype of a Ukrainian: “a civilized” Russian vs. “uncivilized” Ukrainian, top-down view, a look of the “older,” “cultured,” “civilized” on someone “younger” and “uncivilized.”1

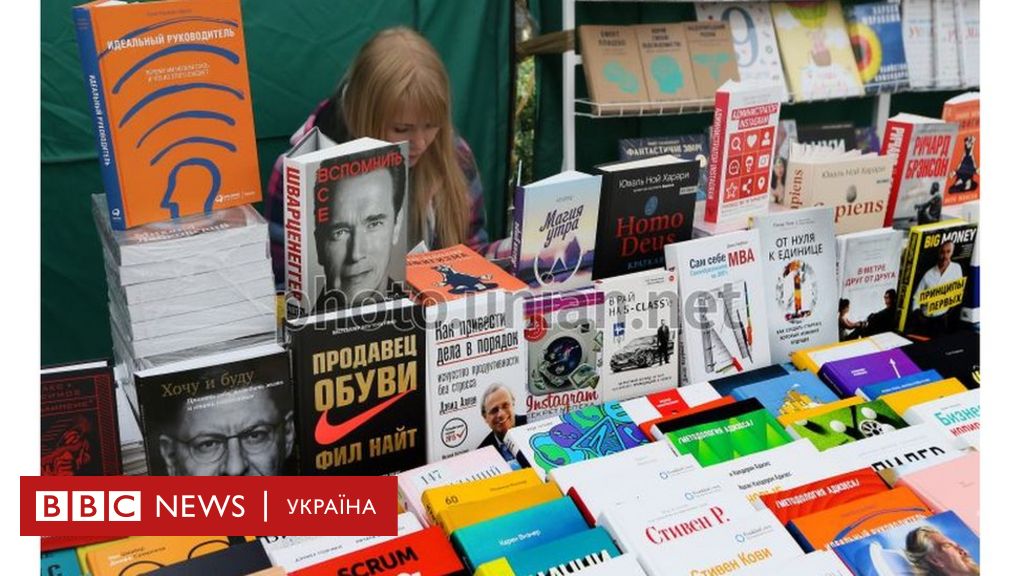

This was reinforced by the politics of the printing press: Until 2014, the book market of Ukraine was filled with Russian books. According to unofficial data, up to 80% of books were in Russian, printed in Ukraine, or imported from Russia.

Після початку конфлікту із Росією українці більше стали читати книжок українською. Але в останні кілька років російська книжка почала зміцнювати свої позиції в Україні. Чому?

Source: www.bbc.com

Even after the beginning of the war with Russia in 2014, Russian authors were still taught in the Ukrainian school program. Moreover, even now, during the total war, the program still contains authors whose works express an imperialistic view of Ukraine that I described before.

Ukrainian TV was also influenced by the “Russian world” and spread its ideas. I checked all the TV shows broadcast on one of the most popular channels: out of 72 shows, 33 were Russian. Eight of them were about the military and explicitly endorsed the Russian army.

This has been slowly changing. In 2018, the share of shows in Ukrainian reached a record 64%, and the percentage of Russian shows dropped to a record low of 7%. By 2020, however, the trend reversed, and the Russian again shows reached almost half of the showtime, and Ukrainian ones took 41%. At the time, six years had already passed since the Russian military invasion of Ukraine, and the cultural invasion has an even longer history.

For a long time, local pro-Russian political elites were dividing Ukrainian society, and did not engage in developing Ukrainian culture. Improving Ukrainian culture was not in the sphere of their interests, nor that of their masters.

Not only was imperialist culture never suppressed, but it was squeezing the Ukrainian culture out of Ukraine through alienation and humiliation. Little did I know how much damage and imperialist ideas I absorbed from Russian literature. I am still coping with the consequences of the years of cultural alienation, and am trying to reopen Ukrainian culture for myself.

I have spent countless hours working to eradicate my “cultural cringe”: the internalized inferiority complex that causes people to devalue their own community’s culture. However, this is the process of healing. I know for sure that I am ready to work on myself so that my culture is never again in danger. This is the price of freedom: cultural and political.